For thousands of years, farmers saved seeds from their crops and replanted them the next season. Seeds were part of the natural cycle — something shared, passed down, and adapted to local conditions. But in recent decades, that’s changed. Today, many of the seeds used to grow our food are owned and controlled by large corporations, protected by patents.

So who really owns our food now? And what does that mean for the farmers who grow it — and the people who eat it?

From Shared Seeds to Private Property

The idea that a seed could be someone’s property might seem strange, but in the 1980s, laws began allowing companies to patent seeds, especially if they had been genetically modified. These patents gave companies the exclusive right to control how the seed is used, including who can plant it, how it’s grown, and whether farmers are allowed to save it.

At first, this applied mainly to genetically engineered seeds, such as those made resistant to pests or herbicides. But now, even some conventionally bred seeds — ones created without genetic modification — are being patented.

The Corporations Behind Our Seeds

A handful of companies now own a large share of the world’s seed supply. The biggest players include:

- Bayer (which bought Monsanto)

- Corteva Agriscience (formerly part of DowDuPont)

- Syngenta (owned by ChemChina)

- BASF

These companies don’t just sell seeds. They also sell the chemicals (like herbicides and pesticides) that go with them. In many cases, the seeds are designed to work only with those chemicals, creating a system where farmers are locked into buying everything from the same company.

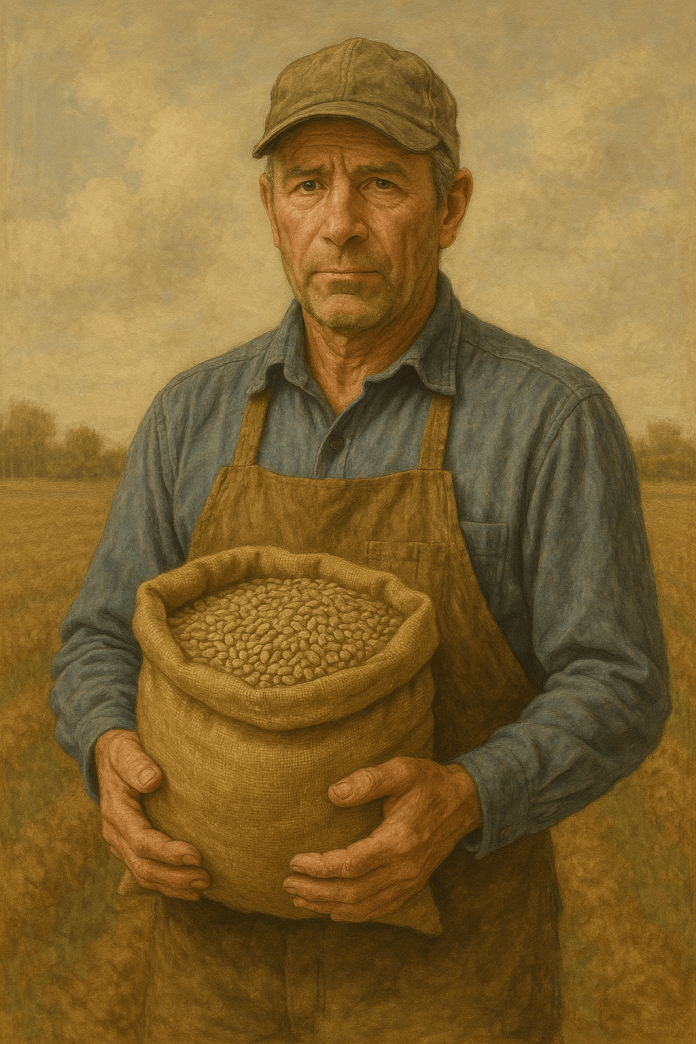

What This Means for Farmers

For many farmers, this new system comes with serious consequences:

- No more saving seeds: Patented seeds can’t legally be saved or replanted. Farmers must buy new ones each year.

- Legal risks: If patented traits show up in a farmer’s field — even accidentally — they can be sued for patent infringement.

- Higher costs: Seed prices have gone up significantly, partly because of patent protections and lack of competition.

- Loss of independence: Farmers who once controlled their own seeds now depend on companies for the most basic part of farming.

One U.S. farmer said it plainly: “We used to be stewards of our seeds. Now we’re just renters.”

Why This Matters for All of Us

It’s not just farmers who are affected. When control of seeds becomes concentrated, it affects the entire food system:

- Less diversity: Companies focus on crops that are profitable at scale. That means fewer varieties and less genetic diversity.

- More vulnerability: If everyone is planting the same patented crops, it increases the risk of crop failures from pests, diseases, or climate change.

- Higher prices and less choice: Fewer companies in control of seeds means less competition — which can lead to higher prices and fewer options for consumers.

In short, when a few companies control the seeds, they control the food.

Are There Alternatives?

Yes — and they’re growing:

- Seed saving and seed banks help preserve traditional and heirloom varieties.

- The Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI) supports seeds that anyone can use, share, and breed freely — like open-source software.

- Farmer-led seed networks are reclaiming control by growing, breeding, and sharing non-patented seeds suited to local needs.

Movements like seed sovereignty — led by groups such as India’s Navdanya — argue that control over seeds is essential to food freedom and democracy.

The Big Question: Who Should Own the Right to Grow Food?

At the heart of the issue is a simple question with big consequences:

Should anyone own the right to grow food?

Patents may help companies recover the cost of research, but when they come at the expense of farmer freedom, food diversity, and public good, we have to ask: is this the right path?

Farmers aren’t just producers — they are caretakers of the land and the seeds. If we want a fair and sustainable food system, they need the freedom to save seeds, grow what works best for their soil and climate, and share their knowledge.

Because when farmers lose control of seeds, we all lose control of the future of our food.